The Parthenon, Athens

The Parthenon, Athens

If there was ever a building you could describe as been there, done that, it'd be the Parthenon. It's hailed as a paragon of architectural beauty and mathematical perfection, but its construction and history proved to be way more complicated.

Likely sprung from misbegotten treasury funds itself, it served as a shrine to the goddess Athena, replete with 40 ft (12 m) gold statue honoring her likeness. As Athens came under the control of various other rulers, it served as a treasury, a church, a mosque, a ruin, and a historical monument.

Each ruling party made changes to fit the culture of their civilization, defacing or stealing sculptures and friezes from the site at will. Yet, it stood nearly intact for about 2,000 years, until a war between the Venetians and the Ottomans left it without a roof in 1687.

Still, as an open-air atrium, and stripped of much of its original adornment, it serves as an example of what humans can create in our best moments.

A (very) brief primer on Greek architecture

Yours Truly

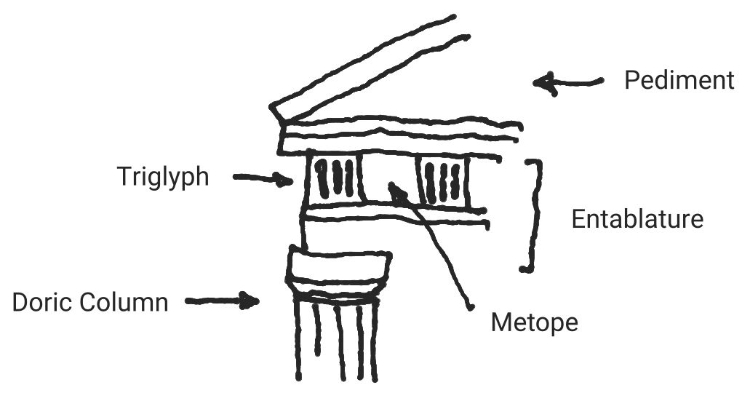

Greek architectural styles were very prescriptive. The Parthenon is mostly an example of the Doric style, identified primarily by its unadorned columns. Above the columns is a rectangular area known as the entablature where much of the building's artistry was displayed.

Doric architecture dictated that the top part of the entablature be divided by triglyphs interspersed with metopes (another place for squirreling away relief sculptures). A triangular pediment capped the building with yet another spot for classical doodling.

Though the nomenclature for Greek buildings can border on the overwhelming, many of the concepts have carried over all the way through our modern times.

All your curves and imperfections

Despite the Greeks' adherence to mathematical rigor in their architecture, the Parthenon is far from a geometrically pure building. The architects understood that the human eye perceives perfectly straight lines as something other than being straight when viewed at particular angles.

In order to preserve the appearance of perfection, the builders used the concept of entasis, or a slight bowing of the columns. In addition, to accommodate the uneven terrain and the same optical illusion of curvature of perfectly straight lines that affected the columns, the stylobate (or main platform) has a nearly imperceptible slop across its length and width.

The slope also assisted with drainage, should a god (or mere mortal) accidentally spill ambrosia in the building.